Putting the lab into the patient to improve chemotherapy success (Day 341)

3rd May 2015

The fight against cancer is ongoing and I have blogged about this before; see ‘Twin track cancer attack’ and ‘Fighting lung cancer with personalised medicine’. Each new discovery we make shines more light onto effective treatments.

Chemotherapy is a type of cancer treatment that uses one or more chemical substances to kill cancerous cells. It can be used in conjunction with other cancer treatments, or given alone. But as there are over 100 different chemotherapy drugs, our ability to prescribe the most effective drug to treat a particular tumour can be difficult.

A new device, developed by chemical engineers from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), US, could provide a solution.

The device, which is about the same size as a grain of rice, is not swallowed or injected, but instead is implanted directly into a cancerous tumour, where it can directly administer small doses of up to 30 different drugs.

One of the MIT research team's senior authors is chemical engineer Robert Langer, who has spent his career pioneering drug delivery; and his team's research was recently published in the journal – Science Translational Medicine: ‘An implantable microdevice to perform high-throughput in vivo drug sensitivity testing in tumors’.

Lead author, Oliver Jonas, a postdoctoral student at MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, thinks that the implant could remove the dilemma of drug selection in cancer treatments.

Oliver said: “You can use it to test a patient for a range of available drugs, and pick the one that works best.”

Cancer drugs typically work by interfering with cell function or by damaging DNA. Recent developments include targeted drugs, designed to kill specific cells. However, it is hard to predict if these drugs will work in a particular individual.

Oliver and the team think their approach is unique as they “Put the lab into the patient”, which allows them to measure the effectiveness of the drug in situ, rather than in a petri dish.

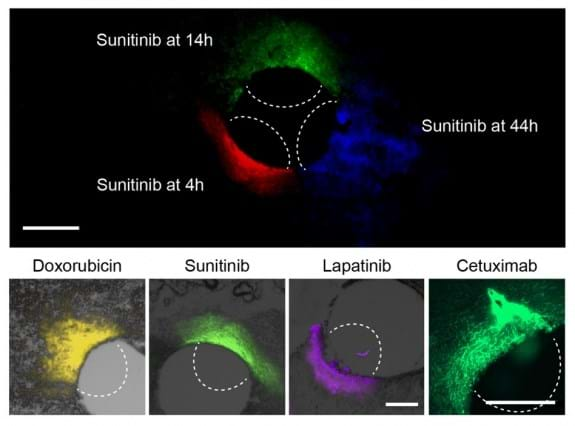

The implant is made from a rigid, crystalline polymer that can be placed directly into a patient’s tumour using a biopsy needle. Once implanted, the drugs seep into the tumour and their effect can be evaluated.

A variety of different drugs can be tested in one implant, which is able to mimic the real doses that are given by standard delivery methods (eg injection). After one day of exposure, the implant is removed, along with a sample of the tissue surrounding it. The tissue is then analysed to assess the effectiveness of the chemotherapy drug.

The implant was tested in mice with human prostate, breast, and melanoma tumours. Such tumours are known to have varying sensitivity to different cancer drugs. In this study, the results reproduced earlier findings..

The researchers tested the device with a particularly aggressive type of breast cancer known as 'triple negative' and found that the tumours responded differently to five of the drugs commonly used to treat them. The most effective was Paclitaxel. They found the same results when delivering these drugs by intravenous injection, supporting their theory that the implant is an accurate predictor of drug sensitivity.

Another member of the research team, Jose Baselga, chief medical officer at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center said: “This device could help us identify the best chemotherapy agents and combinations for every tumour prior to starting systemic administration of chemotherapy, as opposed to making choices based on population-based statistics. This has been a longstanding pursuit of the oncology community and an important step toward our goal of developing precision-based cancer therapy."

The team are now working to make the device easier to read while it is still inside the patient, facilitating faster results. They also plan to launch a clinical trial for breast cancer patients next year.

This work has great potential to enable clinicians to identity the right treatment more rapidly, with significant benefits for cancer patients. I look forward to hearing more about the developments at MIT in the months to come.

If you are working to improve the effectiveness of cancer treatment, get in touch and share your story via the blog.